Things to read...

Here you will find a small selection of articles on various military themes.

So grab yourself a juice or a coffee, get comfortable and start scrolling through this page.

Military Collecting, where to begin?

Military Collecting, where to begin?

1 Military Collecting – Where to begin?

This is the first part of our three-part beginners’ guide looking into collecting, buying and selling militaria.

Are you interested in military history, airplanes, or tanks? Do you enjoy watching war movies? Whatever you like, creating a militaria collection can be an amazing hobby. Perhaps you've already been thinking of starting one but don’t know how or where to begin? A militaria collection is fantastic and always changing as your knowledge and interests evolve. It’s fun to visit shops, flea markets or even go online and buy whatever militaria thing catches your eye, especially when you grab a bargain. And when you’re out of cash it's still fun to window shop or plan your wish list. Many collectors have been collecting since they were kids, but it was when their interest and perhaps pocket money grew that this fun activity turn into a focused hobby. Most collectors also try to stick to collecting one thing, such as badges, buttons, caps, helmets, tinnies, or medals… Or maybe that’s what they want you to think? Often when you see their guy or girl “bunkers” they look like mini museums!

Whatever you want to collect, this hobby is a huge and rewarding area with something for almost every interest and budget. What a great way to enjoy your hobby whilst preserving history and memories. An added bonus if some of your pieces have a personal connection to a family member.

The two questions you need to think about are these: 1. What do I want to collect and 2. Where do I even begin? The first question is a personal choice. Ok, so you have decided on what to collect, now what’s next?! The best advice you could listen to before you start spending your hard-earned cash is to do your homework. Don’t worry this is fun homework! Read the forums and join collectors’ groups on social media or otherwise, buy a good collectors’ reference book or more and go online window shopping at dealer and auction sites. Don’t forget to have a good drool at other people’s online collections too. That way you can build up a good feel for the specific genre. Identify the different models and learn about their design characteristics to see which features, shapes or materials were used at a certain time. Compare photos you find out in the www so you can learn to notice the differences between originals and fakes, reproductions, or refurbs. Don’t be shy in asking questions but don’t bombard the other members too much. Remember, whilst collectors like to share tips and opinions, they also had to learn their knowledge and read books. Too many questions get annoying, especially for those who learnt the hard way. Later on, when your knowledge grows you can also share it on the forums.

Militaria categories are different but can also be similar in some ways. Confused? Basically, whatever it is, collecting Second World War items will cost you more than post-war items, or even in some cases World War I items. Post-war is the time between 1945 and the present day. Out of all modern militaria collecting, vehicles and machines excluded, WW2 German items can be the most expensive. Which is why there are so many fakes or reworked pieces out there aimed at grabbing your money, so beware! Some are so well done that identifying them is a challenge.

Service medals can be acquired for reasonable prices compared to bravery medals, which can start to get extremely pricey. Don’t even ask me what an original Victoria Cross would cost to buy, if you could even find one for sale. There are plenty of repros out there to fill the collection gap until a decent original turns up, or fakes to trick the honest collector out of an inheritance.

Badge or button collecting is popular and like medals take up less space to store or display. Most examples, even WW2, can be bought for low prices, but be careful of restrikes and copies. More common styles or regiments are quite easy to find and won’t hurt your bank balance much. Rarer pattern patches, styles or dress cap badges with silver elements can start to get pricey though.

Let’s take a closer look at military helmets. Many collectors want to start with WW2 helmets straight away. Whilst that is all fine and good these helmets are not cheap and are perhaps the worse minefield out there, with the many fakes littering the market. Before you take the plunge then, why not sharpen your teeth on a post-war helmet collection?

The benefits are numerous. They are cheaper for a start. There are more interesting varieties to explore and collect, from lots of different countries. Learning about them, analysing their details and history can allow you to hone your skills and learn the hobby. Then when you are ready to progress to WW2 helmets you will be thinking more like a collector and won’t buy the first dodgy attactractively priced helmet you get offered, hoping and wanting it to be the real thing. Learning the hobby can include knowing where to buy pieces, what to look out for, where to seek advice, where to find references for it, which reference books, where to share/display your piece online, how to examine it (find markings etc), and what your feel you should pay.

Collecting post-war steel helmets is a good way to break into this hobby. I am talking about 1960/70/80/90s Austrian, Belgium, British, Eastern European, French, German, Swedish, and Swiss helmets. These are mostly neglected by more advanced collectors and can still be bought cheaply. Whilst they do not have the wow factor of WW2 don’t get fooled into thinking they are a boring genre. There are many different variations, even helmet covers and nets. Especially with the European M1 copies of the cool looking WWII US M1 helmet. These were made and worn by several countries from the end of the 1950s and even used in war movies. Post-war steel airborne helmets are getting more expensive, especially the British examples which were used up until the Falklands War. However, the 1960s German paratrooper helmet is a cheaper alternative. US Vietnam helmets, both ground troops and airborne, are also on the price rise. Argentinian helmets used during the Falkland’s War conflict are perhaps at the top of the post-war steel helmet price range.

Composite helmets are relatively cheap to get hold off, especially the British Mk6 and Mk6A models. The British Mk7 is a little more expensive, as are paratrooper examples. The early composite British paratrooper helmets used from the Falkland’s War period can get expensive. Most composite helmet prices remain reasonable, although Austrian examples are higher as they remain in service and do not come up for sale that often. Of course, surplus current issue helmets are more expensive than older decommissioned models but not on the WW2 price scale.

Prices start to rise when moving onto standard Second World War British, Commonwealth, French… and US helmets. As well as civilian pattern WW2 German Police or Fire service helmets. British or US pots with unit markings can at least double their price. Although with all collecting the price depends on luck on the day, what it is and where you buy it from. WW2 South African steel helmets are getting more expensive too, over the 100 mark, as are the rarer British desert helmets. Now moving towards the higher end are standard WW2 German helmets without decals, then those with decals, and onto the US helmets with fixed chinstrap bales and desirable cardboard Hawley liners. Then WWII British airborne helmets and US paratrooper helmets, US Medic helmets, and perhaps the most expensive of all are the WW2 German paratrooper helmets.

In some ways it's the same story with British Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force peaked visor caps. Post-war caps, especially more modern ones tend to sell for very reasonable prices, especially the more common regiments or enlisted men’s hats. Senior officer caps and ones made by tailors start to get pricier. WW2 caps are of course more expensive, even standard caps and junior officer caps. More unusual regiments and senior officers’ caps, like Generals, Admirals and Air Marshal are starting to reach high prices, in the mid 100s, since they do not come up for sale that often. As with their helmets WW2 German hats and caps are priced around the same as British senior officer caps.

Generally, whatever you are collecting, know your hobby well. Be sure to read up on your chosen subject to avoid burning your fingers on the fakes, reproductions and reworked pieces. Make a collection you can be proud to show off and have.

We hope you found this intro helpful. Please read the next instalment and let us know your thoughts on our social media.

This is the first part of our three-part beginners’ guide looking into collecting, buying and selling militaria.

Are you interested in military history, airplanes, or tanks? Do you enjoy watching war movies? Whatever you like, creating a militaria collection can be an amazing hobby. Perhaps you've already been thinking of starting one but don’t know how or where to begin? A militaria collection is fantastic and always changing as your knowledge and interests evolve. It’s fun to visit shops, flea markets or even go online and buy whatever militaria thing catches your eye, especially when you grab a bargain. And when you’re out of cash it's still fun to window shop or plan your wish list. Many collectors have been collecting since they were kids, but it was when their interest and perhaps pocket money grew that this fun activity turn into a focused hobby. Most collectors also try to stick to collecting one thing, such as badges, buttons, caps, helmets, tinnies, or medals… Or maybe that’s what they want you to think? Often when you see their guy or girl “bunkers” they look like mini museums!

Whatever you want to collect, this hobby is a huge and rewarding area with something for almost every interest and budget. What a great way to enjoy your hobby whilst preserving history and memories. An added bonus if some of your pieces have a personal connection to a family member.

The two questions you need to think about are these: 1. What do I want to collect and 2. Where do I even begin? The first question is a personal choice. Ok, so you have decided on what to collect, now what’s next?! The best advice you could listen to before you start spending your hard-earned cash is to do your homework. Don’t worry this is fun homework! Read the forums and join collectors’ groups on social media or otherwise, buy a good collectors’ reference book or more and go online window shopping at dealer and auction sites. Don’t forget to have a good drool at other people’s online collections too. That way you can build up a good feel for the specific genre. Identify the different models and learn about their design characteristics to see which features, shapes or materials were used at a certain time. Compare photos you find out in the www so you can learn to notice the differences between originals and fakes, reproductions, or refurbs. Don’t be shy in asking questions but don’t bombard the other members too much. Remember, whilst collectors like to share tips and opinions, they also had to learn their knowledge and read books. Too many questions get annoying, especially for those who learnt the hard way. Later on, when your knowledge grows you can also share it on the forums.

Militaria categories are different but can also be similar in some ways. Confused? Basically, whatever it is, collecting Second World War items will cost you more than post-war items, or even in some cases World War I items. Post-war is the time between 1945 and the present day. Out of all modern militaria collecting, vehicles and machines excluded, WW2 German items can be the most expensive. Which is why there are so many fakes or reworked pieces out there aimed at grabbing your money, so beware! Some are so well done that identifying them is a challenge.

Service medals can be acquired for reasonable prices compared to bravery medals, which can start to get extremely pricey. Don’t even ask me what an original Victoria Cross would cost to buy, if you could even find one for sale. There are plenty of repros out there to fill the collection gap until a decent original turns up, or fakes to trick the honest collector out of an inheritance.

Badge or button collecting is popular and like medals take up less space to store or display. Most examples, even WW2, can be bought for low prices, but be careful of restrikes and copies. More common styles or regiments are quite easy to find and won’t hurt your bank balance much. Rarer pattern patches, styles or dress cap badges with silver elements can start to get pricey though.

Let’s take a closer look at military helmets. Many collectors want to start with WW2 helmets straight away. Whilst that is all fine and good these helmets are not cheap and are perhaps the worse minefield out there, with the many fakes littering the market. Before you take the plunge then, why not sharpen your teeth on a post-war helmet collection?

The benefits are numerous. They are cheaper for a start. There are more interesting varieties to explore and collect, from lots of different countries. Learning about them, analysing their details and history can allow you to hone your skills and learn the hobby. Then when you are ready to progress to WW2 helmets you will be thinking more like a collector and won’t buy the first dodgy attactractively priced helmet you get offered, hoping and wanting it to be the real thing. Learning the hobby can include knowing where to buy pieces, what to look out for, where to seek advice, where to find references for it, which reference books, where to share/display your piece online, how to examine it (find markings etc), and what your feel you should pay.

Collecting post-war steel helmets is a good way to break into this hobby. I am talking about 1960/70/80/90s Austrian, Belgium, British, Eastern European, French, German, Swedish, and Swiss helmets. These are mostly neglected by more advanced collectors and can still be bought cheaply. Whilst they do not have the wow factor of WW2 don’t get fooled into thinking they are a boring genre. There are many different variations, even helmet covers and nets. Especially with the European M1 copies of the cool looking WWII US M1 helmet. These were made and worn by several countries from the end of the 1950s and even used in war movies. Post-war steel airborne helmets are getting more expensive, especially the British examples which were used up until the Falklands War. However, the 1960s German paratrooper helmet is a cheaper alternative. US Vietnam helmets, both ground troops and airborne, are also on the price rise. Argentinian helmets used during the Falkland’s War conflict are perhaps at the top of the post-war steel helmet price range.

Composite helmets are relatively cheap to get hold off, especially the British Mk6 and Mk6A models. The British Mk7 is a little more expensive, as are paratrooper examples. The early composite British paratrooper helmets used from the Falkland’s War period can get expensive. Most composite helmet prices remain reasonable, although Austrian examples are higher as they remain in service and do not come up for sale that often. Of course, surplus current issue helmets are more expensive than older decommissioned models but not on the WW2 price scale.

Prices start to rise when moving onto standard Second World War British, Commonwealth, French… and US helmets. As well as civilian pattern WW2 German Police or Fire service helmets. British or US pots with unit markings can at least double their price. Although with all collecting the price depends on luck on the day, what it is and where you buy it from. WW2 South African steel helmets are getting more expensive too, over the 100 mark, as are the rarer British desert helmets. Now moving towards the higher end are standard WW2 German helmets without decals, then those with decals, and onto the US helmets with fixed chinstrap bales and desirable cardboard Hawley liners. Then WWII British airborne helmets and US paratrooper helmets, US Medic helmets, and perhaps the most expensive of all are the WW2 German paratrooper helmets.

In some ways it's the same story with British Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force peaked visor caps. Post-war caps, especially more modern ones tend to sell for very reasonable prices, especially the more common regiments or enlisted men’s hats. Senior officer caps and ones made by tailors start to get pricier. WW2 caps are of course more expensive, even standard caps and junior officer caps. More unusual regiments and senior officers’ caps, like Generals, Admirals and Air Marshal are starting to reach high prices, in the mid 100s, since they do not come up for sale that often. As with their helmets WW2 German hats and caps are priced around the same as British senior officer caps.

Generally, whatever you are collecting, know your hobby well. Be sure to read up on your chosen subject to avoid burning your fingers on the fakes, reproductions and reworked pieces. Make a collection you can be proud to show off and have.

We hope you found this intro helpful. Please read the next instalment and let us know your thoughts on our social media.

Military Collecting, how to buy it?

Military Collecting, how to buy it?

2 Military Collecting – How to buy it?

In this the second of our three-part beginners’ guide we’ll look into buying militaria.

Buying militaria is a minefield…. Yes, I do like to use that word a lot! But it really is. There are lots of dealer websites online, not to mention the free listings sites and auction sites. There are also the good old-fashioned places, such as antique shops, militaria shops, junk shops, surplus stores, flea-markets, car boot sales… where you can even get face to face with a piece, get it in your hands and even see if it smells right.

Generally though, most “real” places can be a bit hit or miss, especially if you are looking for a specific piece. They can also be surprising and rewarding. Flea markets and car boot sales more so as the sellers often do not know what jem they are selling. Dealers on the other hand most certainly do, or think they do, and tend to offer pieces for sale at the going rate or more expensive.

It is also interesting when you think about the word “rare”. What does that even mean? Being rare doesn’t necessarily mean it is valuable. Let’s take a 1958 Austrian M1 helmet clone liner. These fibre liners were fragile and soon replaced by thermoplastic ones, so an early liner is hard to find. These are therefore rare but alas not that valuable, especially if you compare one to an original US wartime liner.

Also, when you collect a genre, say for example British WWII visor caps, you will eventually discover which examples are more common and affordable and which less so. Most dealers deal in a mixed range of militaria and may not come across a piece like what you are collecting that often, so may list it for sale at a high price reflecting what they think is rare and… expensive. For you this piece may be a bog standard piece, interesting of course but overly priced.

There is a distinct difference between buying in real and buying online. Both have advantages and disadvantages. In some ways real shopping gives you more control over the piece, especially when you can see it with your own eyes, in the light of day. On the other hand, online shopping opens you up to a world of wonderful militaria options, where you aren’t just limited to what the dealer has standing in front of you. The big disadvantage of this however is that you cannot grab the piece before dishing out the doe.

So, when you find a piece in real you should take the time to examine it in your hands. Does the condition of the parts match to each other or does one part look newer or freshly painted? Are there any replacement pieces? Are screws or attachments loose? Does it smell “old” or new? Is it soft or brittle? Do the markings look consistent with the overall piece? Are any painted markings going over a rust patch? Does it seem too cheap? … Depending on what it is, these are the sorts of questions you should be thinking about.

Maybe you could ask the shop to hold a piece for a few days, in which case you can do some research or ask a few collector friends for their opinions. Remember that most sellers are not experts in your collecting field so there is always a risk that a piece might not be what they think it is, often through np fault of their own.

For online shopping the guides are roughly the same, apart from viewing through a computer, tablet or smart phone screen. As you carefully examine all the listing photos think about the same questions as above. Read the description well and don’t be afraid to ask questions or for more information about its background, a certain marking or feature. Don’t be afraid as well to ask for more photos. Photos that show closeups, badge details, decals, markings etc.

Use the opportunity whilst the piece is still within the auction time or in your wishlist / watchlist to research it and ask other collector’s their opinions (without sharing where the item is up for sale… don’t want someone else snapping it up if it is indeed a good one) and read up on the subject to see if everything makes sense. Unless you really know your stuff or if it is from a reputable dealer then be very cautious of buying higher end pieces. While this sometimes works out there is also a chance you’ll get burnt.

If you don’t ask you don’t know, so it may be worth asking if a dealer or seller will negotiate on the price, accept a trade, or even part exchange. Take the sales pitch with a pinch of salt. Fall for object not story. What does your gut say over your heart?

Disclaimer: So, to sum up, there is no fool proof guide to buying militaria or how to avoid being a victim of scam artists. Especially when there is a world of suspicious militaria pieces out there. In collecting, the more informed and knowledgeable you are the better. The information here is a just a basic guide on the subject, the ultimate responsibility and decision on whether you want to buy a piece or not is up to you. You are the one looking at buying the specific piece and know the details of the listing, so use your judgment.

We hope you found this helpful and please read the next instalment in the series of buying militaria. Let us know your thoughts on our social media.

In this the second of our three-part beginners’ guide we’ll look into buying militaria.

Buying militaria is a minefield…. Yes, I do like to use that word a lot! But it really is. There are lots of dealer websites online, not to mention the free listings sites and auction sites. There are also the good old-fashioned places, such as antique shops, militaria shops, junk shops, surplus stores, flea-markets, car boot sales… where you can even get face to face with a piece, get it in your hands and even see if it smells right.

Generally though, most “real” places can be a bit hit or miss, especially if you are looking for a specific piece. They can also be surprising and rewarding. Flea markets and car boot sales more so as the sellers often do not know what jem they are selling. Dealers on the other hand most certainly do, or think they do, and tend to offer pieces for sale at the going rate or more expensive.

It is also interesting when you think about the word “rare”. What does that even mean? Being rare doesn’t necessarily mean it is valuable. Let’s take a 1958 Austrian M1 helmet clone liner. These fibre liners were fragile and soon replaced by thermoplastic ones, so an early liner is hard to find. These are therefore rare but alas not that valuable, especially if you compare one to an original US wartime liner.

Also, when you collect a genre, say for example British WWII visor caps, you will eventually discover which examples are more common and affordable and which less so. Most dealers deal in a mixed range of militaria and may not come across a piece like what you are collecting that often, so may list it for sale at a high price reflecting what they think is rare and… expensive. For you this piece may be a bog standard piece, interesting of course but overly priced.

There is a distinct difference between buying in real and buying online. Both have advantages and disadvantages. In some ways real shopping gives you more control over the piece, especially when you can see it with your own eyes, in the light of day. On the other hand, online shopping opens you up to a world of wonderful militaria options, where you aren’t just limited to what the dealer has standing in front of you. The big disadvantage of this however is that you cannot grab the piece before dishing out the doe.

So, when you find a piece in real you should take the time to examine it in your hands. Does the condition of the parts match to each other or does one part look newer or freshly painted? Are there any replacement pieces? Are screws or attachments loose? Does it smell “old” or new? Is it soft or brittle? Do the markings look consistent with the overall piece? Are any painted markings going over a rust patch? Does it seem too cheap? … Depending on what it is, these are the sorts of questions you should be thinking about.

Maybe you could ask the shop to hold a piece for a few days, in which case you can do some research or ask a few collector friends for their opinions. Remember that most sellers are not experts in your collecting field so there is always a risk that a piece might not be what they think it is, often through np fault of their own.

For online shopping the guides are roughly the same, apart from viewing through a computer, tablet or smart phone screen. As you carefully examine all the listing photos think about the same questions as above. Read the description well and don’t be afraid to ask questions or for more information about its background, a certain marking or feature. Don’t be afraid as well to ask for more photos. Photos that show closeups, badge details, decals, markings etc.

Use the opportunity whilst the piece is still within the auction time or in your wishlist / watchlist to research it and ask other collector’s their opinions (without sharing where the item is up for sale… don’t want someone else snapping it up if it is indeed a good one) and read up on the subject to see if everything makes sense. Unless you really know your stuff or if it is from a reputable dealer then be very cautious of buying higher end pieces. While this sometimes works out there is also a chance you’ll get burnt.

If you don’t ask you don’t know, so it may be worth asking if a dealer or seller will negotiate on the price, accept a trade, or even part exchange. Take the sales pitch with a pinch of salt. Fall for object not story. What does your gut say over your heart?

Disclaimer: So, to sum up, there is no fool proof guide to buying militaria or how to avoid being a victim of scam artists. Especially when there is a world of suspicious militaria pieces out there. In collecting, the more informed and knowledgeable you are the better. The information here is a just a basic guide on the subject, the ultimate responsibility and decision on whether you want to buy a piece or not is up to you. You are the one looking at buying the specific piece and know the details of the listing, so use your judgment.

We hope you found this helpful and please read the next instalment in the series of buying militaria. Let us know your thoughts on our social media.

British army helmets from WW1 until 2022

British army helmets from WW1 until 2022

Quick Identification of British Military Helmets, 1917 until 2022.

Helmet collecting is one of the hottest areas of military collecting and can be very confusing to the newcomer or young collector. Military helmets are what inspired many collectors to turn their military interest into an active serious hobby. What may at first look all the same can in fact make a difference to the age of a helmet and indeed its price. It is also valuable to know the basic differences between helmet models and types, so you can tell if the helmet is original or an incorrect mash-up of different types. This then is meant to be basic introduction and first point of call to learning about British army helmets.

During the First World War, during trench warfare, the need for a modern steel helmet to protect soldiers from shrapnel was first realised. The French M1915 helmet was the first to be developed, followed by the British Mark 1 helmet and its nearly identical American cousin the M1917.

The Mark 1 or Mk.I helmet had a steel shell with a two part leather chinstrap and steel buckle. Its lining was a non-size adjustable black oilcloth skull cap with a rubber ring in the crown. The helmet had makers details and date? Stamped into the brim. A rim was added to later war examples but are not found on early examples. The metal of the helmet feels notably thinner than later period examples. Sometime a hessian helmet cover was worn over the helmet, although most helmets on the collectors’ market are standard examples.

The Mark 2 or Mk.II also had a non-magnetic steel shell with a three part chinstrap consisting of two cloth covered side springs joined by a strip of webbing. The lining was made from black oilcloth with five tongues tied together by a black bootlace. It was sewn to a cardboard frame which was screen to the helmet’s shell crown by a screw through an oilcloth covered dome pad. On early war helmets the pad was oval but later changed to a cross form. Both the steel shell and cardboard frame have a maker’s marking and manufacture date. The steel shell also has a rim around its edging, while the helmet surface could either be smooth or textured. Helmet nets were often worn with the Mk.II helmet and in some cases a unit marking was painted onto the sides.

The Mark 2 was also used by Homefront units, such as Air raid Wardens and ambulance crews and the Home Guard. As such it was painted in colours to match the function it was being used for, such as white or black. Home Guard units were also issued with Mark 2 helmets, but mostly of an inferior metal quality, designated as Mk2B or Mk2Cs, showing holes punched out of their brims to show their sub-standard. An example of which is a 2nd Battalion Worcestershire Home Guard helmet.

The Mark 1* was very similar to the Mark 2 but instead of a steel shell made in the late 1930s or early 1940s, it uses a reissued WW1 vintage steel shell. These helmets appear a little less uniform in form and are rarer and so command a higher value for collectors and dealers.

The Mark 3 or Mk.III helmet was introduced late in the Second World War and was more of a turtle shape than the bowler hat style of the Mark II. Wartime examples, used predominantly by the Canadian Forces and more widespread just after the war, are extremely desirable to collectors. The steel shell tended to use a simplified elasticated chinstrap, which was secured to the shell halfway up the side of the helmet. The lining was as that used on the Mark II helmet. Again, unit markings were sometimes painted to the sides and nets used. A metal rim was also fixed around the helmets edge and makers’ markings found on the helmet.

The Mark 4 or Mk.IV helmet was the same as the Mark 3 but the crown screw was replaced by a pop out rivet, allowing the liner to be easily and quickly removed and the position of the chinstrap attachment points lowered to the near the helmet’s rim. An elasticated one-piece chinstrap was used. Whilst some examples lacked a rim most helmets were fitted with a rim edging.

The unofficially named but referred to by many collectors as the Mark 5 or Mk.V was a slight upgrade to the Mark 4 but featured a better padded lining, which used a cloth covered foam skull cap mounted to a cardboard frame with rubber buffers between the steel shell and liner. The lining also used the cross shaped dome pad. The Mk.IV and V were typical of those used by the British Army in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

During the 1980s and into the 1990s the Mark 5 was gradually replaced by Mark 6 or Mk.6 helmet. The Mark 6 was moulded from green ballistic Kevlar with a olive green webbing three strap chinstrap with black plastic buckles and a black leather chin cup. The lining consisted of a black plastic frame with a front forehead and nape black leather cushion, allowing space for the ears and intercoms. The crown of the head was supported by four olive green nylon webbing straps tied together with a black bootlace. A white paper label with maker’s markings and information was stuck into the helmet. The Mark 6 was worn with a DPM helmet cover, which had elasticated straps for adding foliage in the field. These were either a woodland camo scheme for Europe or desert scheme, as worn during the 1st Gulf War in 1991. Sometimes a unit flash was sewn onto the covers, such as the WFR’s green diamond, which can be seen on a Mk.6 example in the Worcestershire & Sherwood Forester Regiment Gallery, of the Worcestershire Militaria Museum.

The Mark 6A or Mk.6A was similar to the Mark 6 but had some improvements, such as a better netted liner crown section to provide extra head support and improved comfort during more humid climates, as well as a black ballistic nylon shell instead of the previous green. The Mark 6A was also worn with a helmet cover and in some cases an added scrim or net over the top. The Mark 6 and Mark 6A were used in Iraq War and on operations in Afghanistan.

The Mark 7 or Mk.7 was introduced in the late 2000s, during the British involvement in Afghanistan and so was moulded in yellow ballistic nylon. It was also lighter than the Mark 6A with an updated rim profile to improve its practicality out in the field. Its chinstrap and lining were similar to the Mark 6A and there was also the optional extras of comfort pads if the wearer desired such a thing. It also had a black rubber rim around the edge of the helmet with black liner securing screws. The Mark 7 was worn with a DPM helmet cover which was later changed to MTP. Sometimes the foliage straps were removed by the soldier, and/or a scrim or net worn over the top. Some examples also had a unit patch sewn onto the side, as was the case with 2 Mercian.

As of 2022, the current standard British Army helmet is the Virtus Helmet, replacing the Mark 7 in around the mid-2010s. It is lighter than the Mark 7 and has a plastic attachment for night vision apparatus at the front. Like the Mark 7 it is also made from yellow composite while its profile shape makes it more practical and comfortable in the field. The lining resembles a bicycle helmet with light olive green forehead, side and nape pads, that is size adjustable at the rear with a tightening bezel. The chinstrap is tan nylon webbing with matching plastic adjustment clips, buckles and side release chin-cup clip. The chin-cup is also tan leather. The helmet is fitted with a MTP cover that fits snuggly to the helmet, with velcro patches and straps for attaching accessories and foliage. Scrims and nets are also worn over the helmet cover. Whilst not as common as on the previous models, some units do still maintain tradition and wear a removeable flash on their helmets, such as units of the Mercian Regiment.

Hopefully, this basic overview should give you a quick guide to British army helmets and there is a wealth of resources and books out there should it spark your interest to learn more.

Helmet collecting is one of the hottest areas of military collecting and can be very confusing to the newcomer or young collector. Military helmets are what inspired many collectors to turn their military interest into an active serious hobby. What may at first look all the same can in fact make a difference to the age of a helmet and indeed its price. It is also valuable to know the basic differences between helmet models and types, so you can tell if the helmet is original or an incorrect mash-up of different types. This then is meant to be basic introduction and first point of call to learning about British army helmets.

During the First World War, during trench warfare, the need for a modern steel helmet to protect soldiers from shrapnel was first realised. The French M1915 helmet was the first to be developed, followed by the British Mark 1 helmet and its nearly identical American cousin the M1917.

The Mark 1 or Mk.I helmet had a steel shell with a two part leather chinstrap and steel buckle. Its lining was a non-size adjustable black oilcloth skull cap with a rubber ring in the crown. The helmet had makers details and date? Stamped into the brim. A rim was added to later war examples but are not found on early examples. The metal of the helmet feels notably thinner than later period examples. Sometime a hessian helmet cover was worn over the helmet, although most helmets on the collectors’ market are standard examples.

The Mark 2 or Mk.II also had a non-magnetic steel shell with a three part chinstrap consisting of two cloth covered side springs joined by a strip of webbing. The lining was made from black oilcloth with five tongues tied together by a black bootlace. It was sewn to a cardboard frame which was screen to the helmet’s shell crown by a screw through an oilcloth covered dome pad. On early war helmets the pad was oval but later changed to a cross form. Both the steel shell and cardboard frame have a maker’s marking and manufacture date. The steel shell also has a rim around its edging, while the helmet surface could either be smooth or textured. Helmet nets were often worn with the Mk.II helmet and in some cases a unit marking was painted onto the sides.

The Mark 2 was also used by Homefront units, such as Air raid Wardens and ambulance crews and the Home Guard. As such it was painted in colours to match the function it was being used for, such as white or black. Home Guard units were also issued with Mark 2 helmets, but mostly of an inferior metal quality, designated as Mk2B or Mk2Cs, showing holes punched out of their brims to show their sub-standard. An example of which is a 2nd Battalion Worcestershire Home Guard helmet.

The Mark 1* was very similar to the Mark 2 but instead of a steel shell made in the late 1930s or early 1940s, it uses a reissued WW1 vintage steel shell. These helmets appear a little less uniform in form and are rarer and so command a higher value for collectors and dealers.

The Mark 3 or Mk.III helmet was introduced late in the Second World War and was more of a turtle shape than the bowler hat style of the Mark II. Wartime examples, used predominantly by the Canadian Forces and more widespread just after the war, are extremely desirable to collectors. The steel shell tended to use a simplified elasticated chinstrap, which was secured to the shell halfway up the side of the helmet. The lining was as that used on the Mark II helmet. Again, unit markings were sometimes painted to the sides and nets used. A metal rim was also fixed around the helmets edge and makers’ markings found on the helmet.

The Mark 4 or Mk.IV helmet was the same as the Mark 3 but the crown screw was replaced by a pop out rivet, allowing the liner to be easily and quickly removed and the position of the chinstrap attachment points lowered to the near the helmet’s rim. An elasticated one-piece chinstrap was used. Whilst some examples lacked a rim most helmets were fitted with a rim edging.

The unofficially named but referred to by many collectors as the Mark 5 or Mk.V was a slight upgrade to the Mark 4 but featured a better padded lining, which used a cloth covered foam skull cap mounted to a cardboard frame with rubber buffers between the steel shell and liner. The lining also used the cross shaped dome pad. The Mk.IV and V were typical of those used by the British Army in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

During the 1980s and into the 1990s the Mark 5 was gradually replaced by Mark 6 or Mk.6 helmet. The Mark 6 was moulded from green ballistic Kevlar with a olive green webbing three strap chinstrap with black plastic buckles and a black leather chin cup. The lining consisted of a black plastic frame with a front forehead and nape black leather cushion, allowing space for the ears and intercoms. The crown of the head was supported by four olive green nylon webbing straps tied together with a black bootlace. A white paper label with maker’s markings and information was stuck into the helmet. The Mark 6 was worn with a DPM helmet cover, which had elasticated straps for adding foliage in the field. These were either a woodland camo scheme for Europe or desert scheme, as worn during the 1st Gulf War in 1991. Sometimes a unit flash was sewn onto the covers, such as the WFR’s green diamond, which can be seen on a Mk.6 example in the Worcestershire & Sherwood Forester Regiment Gallery, of the Worcestershire Militaria Museum.

The Mark 6A or Mk.6A was similar to the Mark 6 but had some improvements, such as a better netted liner crown section to provide extra head support and improved comfort during more humid climates, as well as a black ballistic nylon shell instead of the previous green. The Mark 6A was also worn with a helmet cover and in some cases an added scrim or net over the top. The Mark 6 and Mark 6A were used in Iraq War and on operations in Afghanistan.

The Mark 7 or Mk.7 was introduced in the late 2000s, during the British involvement in Afghanistan and so was moulded in yellow ballistic nylon. It was also lighter than the Mark 6A with an updated rim profile to improve its practicality out in the field. Its chinstrap and lining were similar to the Mark 6A and there was also the optional extras of comfort pads if the wearer desired such a thing. It also had a black rubber rim around the edge of the helmet with black liner securing screws. The Mark 7 was worn with a DPM helmet cover which was later changed to MTP. Sometimes the foliage straps were removed by the soldier, and/or a scrim or net worn over the top. Some examples also had a unit patch sewn onto the side, as was the case with 2 Mercian.

As of 2022, the current standard British Army helmet is the Virtus Helmet, replacing the Mark 7 in around the mid-2010s. It is lighter than the Mark 7 and has a plastic attachment for night vision apparatus at the front. Like the Mark 7 it is also made from yellow composite while its profile shape makes it more practical and comfortable in the field. The lining resembles a bicycle helmet with light olive green forehead, side and nape pads, that is size adjustable at the rear with a tightening bezel. The chinstrap is tan nylon webbing with matching plastic adjustment clips, buckles and side release chin-cup clip. The chin-cup is also tan leather. The helmet is fitted with a MTP cover that fits snuggly to the helmet, with velcro patches and straps for attaching accessories and foliage. Scrims and nets are also worn over the helmet cover. Whilst not as common as on the previous models, some units do still maintain tradition and wear a removeable flash on their helmets, such as units of the Mercian Regiment.

Hopefully, this basic overview should give you a quick guide to British army helmets and there is a wealth of resources and books out there should it spark your interest to learn more.

The WW2 helmet "Great" escape story!

The WW2 helmet "Great" escape story!

Not without my helmet! The tin helmet escape attempt.

It is mid-war 1942, Singapore has fallen to the Japanese, the British have secured a key victory against the Deutsch Afrika Korps at El Alamein, while the Russians are making an epic stand in Stalingrad which will eventually turn the tide of war on the Eastern Front against the Germans once and for all.

However, for a few inmates at the Italian run Prisoner of War Camp 57, situated near Udine, close to the Italian Slovenian border, all this may have seemed a whole world away as dramatic events were unfolding. 19 brave Australians and New Zealanders were preparing to make their last dash to freedom from a tunnel they had painstakingly dug under the camp, hiding the earth below floorboards in various prison huts.

Amongst the Aussies was Royal Australian Air Force Wireless Operator Eric Canning, who was captured in North Africa in 1941 and now found himself part of the escape team. This was to be Canning's second escape attempt. Armed with only a liberated pickaxe and a stack of Mk.2 steel helmets, to dig and move soil, the escapers worked tirelessly over 6 weeks to burrow a way out of the camp. Despite a few hairy moments during the dig and the escape the tunnel remained undiscovered.

The goal was to head through Northern Italy towards Switzerland, over the Julian Alps, alas this wasn't meant to be. A mixture of bad timing or bad luck saw the escapers recaptured after several days, having had the misfortune to find themselves amongst a recuperating unit of Italian soldiers!

Despite the attempt failing the courage and determination of these fine young men should not be forgotten. Furthermore, the use of tommy helmets as a improvised shovel was ingenious. The design of the British and Commonwealth helmet goes back to the first Brodie helmet developed and introduced in 1916 during the First World War, often referred to as the Battlefield Bowler. Its wide brim and deep crown design with its easily removable oilcloth lining definitely lent itself to POW's task at hand.

The Mk.II tin helmet liner could be removed by unscrewing the crown securing bolt.

You can read the full interview with ABC New's Lucy Shannon and Mr Canning at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-04-23/unsung-veteran-recalls-tin-hat-tunnel-escape/408784.

It is mid-war 1942, Singapore has fallen to the Japanese, the British have secured a key victory against the Deutsch Afrika Korps at El Alamein, while the Russians are making an epic stand in Stalingrad which will eventually turn the tide of war on the Eastern Front against the Germans once and for all.

However, for a few inmates at the Italian run Prisoner of War Camp 57, situated near Udine, close to the Italian Slovenian border, all this may have seemed a whole world away as dramatic events were unfolding. 19 brave Australians and New Zealanders were preparing to make their last dash to freedom from a tunnel they had painstakingly dug under the camp, hiding the earth below floorboards in various prison huts.

Amongst the Aussies was Royal Australian Air Force Wireless Operator Eric Canning, who was captured in North Africa in 1941 and now found himself part of the escape team. This was to be Canning's second escape attempt. Armed with only a liberated pickaxe and a stack of Mk.2 steel helmets, to dig and move soil, the escapers worked tirelessly over 6 weeks to burrow a way out of the camp. Despite a few hairy moments during the dig and the escape the tunnel remained undiscovered.

The goal was to head through Northern Italy towards Switzerland, over the Julian Alps, alas this wasn't meant to be. A mixture of bad timing or bad luck saw the escapers recaptured after several days, having had the misfortune to find themselves amongst a recuperating unit of Italian soldiers!

Despite the attempt failing the courage and determination of these fine young men should not be forgotten. Furthermore, the use of tommy helmets as a improvised shovel was ingenious. The design of the British and Commonwealth helmet goes back to the first Brodie helmet developed and introduced in 1916 during the First World War, often referred to as the Battlefield Bowler. Its wide brim and deep crown design with its easily removable oilcloth lining definitely lent itself to POW's task at hand.

The Mk.II tin helmet liner could be removed by unscrewing the crown securing bolt.

You can read the full interview with ABC New's Lucy Shannon and Mr Canning at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-04-23/unsung-veteran-recalls-tin-hat-tunnel-escape/408784.

Military helmet trends

Military helmet trends

Helmet Trends

Infantry combat helmets have come a long way since their development a hundred years ago. Whilst the first examples were made from steel, since the 1980s ballistic nylon, kevlar and composites have taken preference. With the continual advance of technology modern infantry helmets are lighter, more comfortable and have better chinstraps. Helmets are now designed to accommodate the various comms and equipment used by front-line troops. The sci-fi fantasies of tomorrow may not be that far away after all.

Helmet covers have also faced changing trends, even prior to the Great War. Worn piecemeal by various units in various conflicts it was during the Vietnam War that their importance was fully recognised. They have now become as essential and integral a part of the helmet as the lining itself.

Focusing on the First World War and the French M1915, currently celebrating its centenary year, it is clear to see just why a standard protective helmet for infantry was so paramount. The initial offensives of the war had stalled into a state of trench warfare and the wounds inflicted from artillery shrapnel and ricocheting bullets were devastating. A reality that had to be quickly addressed.

However, the idea of an infantry helmet is no new one and the key designs of the 20th century may not seem so different from those used hundreds of years before, albeit with improved linings, chinstraps and better grade steel. The face of war has changed but the basic need for adequate head protection for those fighting had not.

The Romans in particular embraced this concept. Their uniformed legions sporting identical helmets, armour and shields, gave a distinct appearance of an organised “modern” army and no doubt made a vivid psychological effect on their enemy, even before battle commenced. This was long before the idea of a professional army had even taken root.

The Roman centurion helmet, and perhaps even its Greek forefather, offered its wearer a basic level of protection for the face and neck, without impairing their senses. A principle and acknowledgement that would continue through the ages.

Viking helmets, as well as those of the Saxons and Normans offered much the same protection as that of the Romans, although now the emphasis was more on protecting the crown of the head and face from blows and projectiles. Yet it is the helmets of the medieval period that bare most resemblance to the first modern infantry helmets.

During the 18th and early 19th century in particular, a metal helmet for infantry fell out of favour over tricorns and shakos. Even as a recent as the 20th century the fashion leaned towards cloth, pith and leather helmets, and it is incredible to think that during the First World War the spiked German leather Pickelhaube was used on the frontline.

In 1915 a helmet development process was sparked across the warring nations. The French kicked off with the M1915. A small light weighted helmet resembling a shrunken cavalry or fireman's helmet. It offered front and rear peak protection, as well as a comb re-enforcing the crown. The ears, lower face, back of the head, and nape were left free. It's style bared slight resemblance to the medieval Morian helmet favoured by Spain and the Vatican's Swiss Guard. Whilst it did not offer an all round protection, it was practically sized with a comfortable leather lining that did not impair its wearer's vision or hearing.

The British were quick to follow suit, with their Brodie helmet. Distinctly gentleman like in appearance its domed crown was surrounded by a wide brim all the way around, very similar to the medieval Kettle helmet. Like the M1915 it did not seek to impair the wearer's senses but on the other hand its protection was limited to above and deflection. The skullcap lining was made of oilcloth and although cheaper than its French cousin, was less comfortable and ill fitting. A US made variant was introduced to the US Army in 1917.

Perhaps the most successful in terms of protection was the German M1916 steel helmet. In a sense a very modern combat helmet for its period and a leap ahead from the imperial looking Pickelhaubes. The core profile of the M16 can still be seen in modern composite helmets. The helmet is somewhat heavier and larger than the French and British examples due to its deep dome crown and large side skirt that wraps around the rear, protecting the wearer's ears and nape. A shallower peak also offers some protection over the face. Similar perhaps to medieval Barbuta. The helmet also featured a three pad liner. Aside from its bulk and weight its protective sides impaired the wearer's hearing.

During the inter-war years these helmets underwent improvements and developments but in essence the original design ideas remained. The French M1915 developed into the M1926, with one piece metal shell and a suspended lining system. The British Mk.1 became the MK.2, with an vastly improved lining and metal shell. While the M1916 became the M1935, a more compact sized helmet with a cutdown skirt and an eight tongue leather lining

The United States was also active during the inter-war period, searching for a new infantry combat helmet that would offer fuller head protection and less impairment. The result was the fantastic and versatile M1 helmet, which went on to serve until the advent of composite helmets. The M1 can perhaps boast of being the longest serving army helmet. During its development, the experimental helmets for the M1 bare close resemblance to the medieval Sallet helmet.

Infantry combat helmets have come a long way since their development a hundred years ago. Whilst the first examples were made from steel, since the 1980s ballistic nylon, kevlar and composites have taken preference. With the continual advance of technology modern infantry helmets are lighter, more comfortable and have better chinstraps. Helmets are now designed to accommodate the various comms and equipment used by front-line troops. The sci-fi fantasies of tomorrow may not be that far away after all.

Helmet covers have also faced changing trends, even prior to the Great War. Worn piecemeal by various units in various conflicts it was during the Vietnam War that their importance was fully recognised. They have now become as essential and integral a part of the helmet as the lining itself.

Focusing on the First World War and the French M1915, currently celebrating its centenary year, it is clear to see just why a standard protective helmet for infantry was so paramount. The initial offensives of the war had stalled into a state of trench warfare and the wounds inflicted from artillery shrapnel and ricocheting bullets were devastating. A reality that had to be quickly addressed.

However, the idea of an infantry helmet is no new one and the key designs of the 20th century may not seem so different from those used hundreds of years before, albeit with improved linings, chinstraps and better grade steel. The face of war has changed but the basic need for adequate head protection for those fighting had not.

The Romans in particular embraced this concept. Their uniformed legions sporting identical helmets, armour and shields, gave a distinct appearance of an organised “modern” army and no doubt made a vivid psychological effect on their enemy, even before battle commenced. This was long before the idea of a professional army had even taken root.

The Roman centurion helmet, and perhaps even its Greek forefather, offered its wearer a basic level of protection for the face and neck, without impairing their senses. A principle and acknowledgement that would continue through the ages.

Viking helmets, as well as those of the Saxons and Normans offered much the same protection as that of the Romans, although now the emphasis was more on protecting the crown of the head and face from blows and projectiles. Yet it is the helmets of the medieval period that bare most resemblance to the first modern infantry helmets.

During the 18th and early 19th century in particular, a metal helmet for infantry fell out of favour over tricorns and shakos. Even as a recent as the 20th century the fashion leaned towards cloth, pith and leather helmets, and it is incredible to think that during the First World War the spiked German leather Pickelhaube was used on the frontline.

In 1915 a helmet development process was sparked across the warring nations. The French kicked off with the M1915. A small light weighted helmet resembling a shrunken cavalry or fireman's helmet. It offered front and rear peak protection, as well as a comb re-enforcing the crown. The ears, lower face, back of the head, and nape were left free. It's style bared slight resemblance to the medieval Morian helmet favoured by Spain and the Vatican's Swiss Guard. Whilst it did not offer an all round protection, it was practically sized with a comfortable leather lining that did not impair its wearer's vision or hearing.

The British were quick to follow suit, with their Brodie helmet. Distinctly gentleman like in appearance its domed crown was surrounded by a wide brim all the way around, very similar to the medieval Kettle helmet. Like the M1915 it did not seek to impair the wearer's senses but on the other hand its protection was limited to above and deflection. The skullcap lining was made of oilcloth and although cheaper than its French cousin, was less comfortable and ill fitting. A US made variant was introduced to the US Army in 1917.

Perhaps the most successful in terms of protection was the German M1916 steel helmet. In a sense a very modern combat helmet for its period and a leap ahead from the imperial looking Pickelhaubes. The core profile of the M16 can still be seen in modern composite helmets. The helmet is somewhat heavier and larger than the French and British examples due to its deep dome crown and large side skirt that wraps around the rear, protecting the wearer's ears and nape. A shallower peak also offers some protection over the face. Similar perhaps to medieval Barbuta. The helmet also featured a three pad liner. Aside from its bulk and weight its protective sides impaired the wearer's hearing.

During the inter-war years these helmets underwent improvements and developments but in essence the original design ideas remained. The French M1915 developed into the M1926, with one piece metal shell and a suspended lining system. The British Mk.1 became the MK.2, with an vastly improved lining and metal shell. While the M1916 became the M1935, a more compact sized helmet with a cutdown skirt and an eight tongue leather lining

The United States was also active during the inter-war period, searching for a new infantry combat helmet that would offer fuller head protection and less impairment. The result was the fantastic and versatile M1 helmet, which went on to serve until the advent of composite helmets. The M1 can perhaps boast of being the longest serving army helmet. During its development, the experimental helmets for the M1 bare close resemblance to the medieval Sallet helmet.

Diverse uses of military helmets

Diverse uses of military helmets

10 other uses of military helmets

First introduced in 1915 the modern military helmet has seen many advances and developments over its long life, both minor and significant, but perhaps the most significant was the change over from anti-magnetic steel to ballistic composite materials during the 1980s.

Within the military the humble helmet has assumed many roles, from the front line to civil defence, however, perhaps this list of 10 alternative uses might surprise you.

Number 1

At number one we have perhaps the most iconic use of military helmets, outside the military of course. What self respecting 1960s biker gang would be complete without their German Stahlhelm, with or without iron cross decals and dare I say Viking horns.

Number 2

OK, I admit that I may be scrapping the barrel a little. With the increased interest in airsoft over the last decade, ex-army and even market ready Navy Seal styled compo helmets have been flooding the market aimed at your average airsofter or paintballer.

Number 3

With the introduction of a new helmet model or improved materials it has been known for old helmets, or in the case of the M1 helmet, liners to be refurbished and sold as kids toys, this was especially obvious during the Second World War.

Number 4

At the end of the Second World War with the mass devastation of cities and industry across Western Europe and the obvious lack of raw metal, basis necessities such as cooking pots and colanders were in short supply. With the vast amount of German helmets suddenly surplus to requirement combined with the resourcefulness of a few a solution to this problem was soon realised.

All manner of German helmets from standard M40s to Gladiator helmets and the now prized helmet M38 Fallschirmjäger were transformed into cookware. It is interesting to note that such pieces were either refurbished in their existing military form or clipped and repressed to offer a more uniformed look. Videos circulated on YouTube show this happening in Holland, while the German company BÖWE Textile Cleaning can trace it routes back to 1945, when they produced cooking pots from old helmets.

Number 5

Similarly to re-using surplus helmet stocks as kitchen equipment, although not on such a large scale, farmers and the like would often block up airvents and liner attaching holes on discarded helmets, add a crude handle and use the helmet for all manner of things, as can be observed on this example which was used as a pig food scoop by a French farmer.

Number 6

It has been known for a number of old military helmets to be used as flower pots or hanging baskets. Again this was more down to individual resourcefulness than as a commercial venture.

Number 7

Another resourceful solution, which may also be seen as war-art along the likes of re-worked WW1 shell casings, may have its merits when displayed in the War Room or Bunker next to your prized collection, are those lamps which feature an old helmet shell as the lampshade. Again it appears to be less of a commercial venture and more individual inventiveness.

Number 8

Love them or hate them, art installations are not just about being pleasing to the eye but often make a bold or controversial statement. When such an artwork uses old, collectable and in some cases valuable helmets then it might be seen as a step too far for the dedicated collector. Cindy Kane's Helmet Project is one such example which uses a variety of suspended US M1 helmets, including examples from World War Two and Vietnam. Her installation aims to draw attention to the work and sacrifices of war correspondents.

Number 9

Movie props! Modern war movies aside, which tend to use fibre glass helmets that look the part, rather than surplus or originals. Many postwar films and TV series used surplus helmets in one form or another, regardless of genre. Although the costume designers of Star Wars developed their characters' helmets from scratch, (which can be read at tstarwasdss website), the appearance of certain helmets in the production have a distinct military appearance, particularly in the case of the German WW1 Stahlhelm and Darth Vader's helmet.

Number 10

Last but by no means least, museums and collections. Military themed museums serve a vital purpose of not only recognising our past history and importantly the sacrifices made by those that fought, and in most cases died, but also on social aspects regarding how times, fashion, technology and attitudes have changed.

Technically speaking this is not necessary another use of the military helmet considering they are remaining in their original forms, but the helmet's new role is to visualise the past with tangible objects. Whilst most helmet collecting is primarily a private past time, perhaps exhibited to only but a few trusted individuals outside the collector's personal circle, it is indeed a preservation of history as with a museum, however, being passionate about their field, private collectors often seek to preserve the personal history of the object, which museums often do not.

This list gives ten of the most obvious alternate uses for military helmets and is by no means concise. I am sure others do usage exist and would be very happy to hear of them. I should also add that I have only chosen to cover the “pot” variety of military helmet, although leather pilot and tanker helmets are indeed a class of military helmet.

First introduced in 1915 the modern military helmet has seen many advances and developments over its long life, both minor and significant, but perhaps the most significant was the change over from anti-magnetic steel to ballistic composite materials during the 1980s.

Within the military the humble helmet has assumed many roles, from the front line to civil defence, however, perhaps this list of 10 alternative uses might surprise you.

Number 1

At number one we have perhaps the most iconic use of military helmets, outside the military of course. What self respecting 1960s biker gang would be complete without their German Stahlhelm, with or without iron cross decals and dare I say Viking horns.

Number 2

OK, I admit that I may be scrapping the barrel a little. With the increased interest in airsoft over the last decade, ex-army and even market ready Navy Seal styled compo helmets have been flooding the market aimed at your average airsofter or paintballer.

Number 3

With the introduction of a new helmet model or improved materials it has been known for old helmets, or in the case of the M1 helmet, liners to be refurbished and sold as kids toys, this was especially obvious during the Second World War.

Number 4

At the end of the Second World War with the mass devastation of cities and industry across Western Europe and the obvious lack of raw metal, basis necessities such as cooking pots and colanders were in short supply. With the vast amount of German helmets suddenly surplus to requirement combined with the resourcefulness of a few a solution to this problem was soon realised.

All manner of German helmets from standard M40s to Gladiator helmets and the now prized helmet M38 Fallschirmjäger were transformed into cookware. It is interesting to note that such pieces were either refurbished in their existing military form or clipped and repressed to offer a more uniformed look. Videos circulated on YouTube show this happening in Holland, while the German company BÖWE Textile Cleaning can trace it routes back to 1945, when they produced cooking pots from old helmets.

Number 5

Similarly to re-using surplus helmet stocks as kitchen equipment, although not on such a large scale, farmers and the like would often block up airvents and liner attaching holes on discarded helmets, add a crude handle and use the helmet for all manner of things, as can be observed on this example which was used as a pig food scoop by a French farmer.

Number 6

It has been known for a number of old military helmets to be used as flower pots or hanging baskets. Again this was more down to individual resourcefulness than as a commercial venture.

Number 7

Another resourceful solution, which may also be seen as war-art along the likes of re-worked WW1 shell casings, may have its merits when displayed in the War Room or Bunker next to your prized collection, are those lamps which feature an old helmet shell as the lampshade. Again it appears to be less of a commercial venture and more individual inventiveness.

Number 8

Love them or hate them, art installations are not just about being pleasing to the eye but often make a bold or controversial statement. When such an artwork uses old, collectable and in some cases valuable helmets then it might be seen as a step too far for the dedicated collector. Cindy Kane's Helmet Project is one such example which uses a variety of suspended US M1 helmets, including examples from World War Two and Vietnam. Her installation aims to draw attention to the work and sacrifices of war correspondents.

Number 9

Movie props! Modern war movies aside, which tend to use fibre glass helmets that look the part, rather than surplus or originals. Many postwar films and TV series used surplus helmets in one form or another, regardless of genre. Although the costume designers of Star Wars developed their characters' helmets from scratch, (which can be read at tstarwasdss website), the appearance of certain helmets in the production have a distinct military appearance, particularly in the case of the German WW1 Stahlhelm and Darth Vader's helmet.

Number 10

Last but by no means least, museums and collections. Military themed museums serve a vital purpose of not only recognising our past history and importantly the sacrifices made by those that fought, and in most cases died, but also on social aspects regarding how times, fashion, technology and attitudes have changed.

Technically speaking this is not necessary another use of the military helmet considering they are remaining in their original forms, but the helmet's new role is to visualise the past with tangible objects. Whilst most helmet collecting is primarily a private past time, perhaps exhibited to only but a few trusted individuals outside the collector's personal circle, it is indeed a preservation of history as with a museum, however, being passionate about their field, private collectors often seek to preserve the personal history of the object, which museums often do not.

This list gives ten of the most obvious alternate uses for military helmets and is by no means concise. I am sure others do usage exist and would be very happy to hear of them. I should also add that I have only chosen to cover the “pot” variety of military helmet, although leather pilot and tanker helmets are indeed a class of military helmet.

The differences between a US WW2 M1 helmet and an Austrian M75 helmet

The differences between a US WW2 M1 helmet and an Austrian M75 helmet

M1 v M75. An essential comparison between the US M1 and Austrian M75 steel helmets.

Instead of using original period helmets that are valuable and may become damaged from use on the set, many war films tend to use M1 helmet clones to resemble the famous WW2 helmet. Most of the times these are worn in background shots and good repros for close-up. Sometimes however, they are not pushed to the background and their tell-tale chinstraps give them away. The Austrian M1 clone is actually a good and cheap substitute for the American original, especially with its stainless steel rim.

At first glance the post war Austrian M75 steel helmet may appear to be a carbon copy of its Godfather, the original WWII US M1 helmet, upon which it was based. While both helmets feature many similarities, such as swivel bales, sewn on chinstraps and a stainless steel rim, it is the details of such that makes comparison between the two fairly easy.

If we focus on the shell first, it is easy to notice that the M1 features cork textured dark green paint as opposed to the M75 which is notable smoother and painted green grey in colour. The front peak and side flared rims on the M1 are more pronounced while the M75 also exhibits a slightly lower profile.

The stainless rims differ as well. On the M75 the rim is quite narrow and joins at the rear, while on the M1 it is wider and flatter, joining at the front. Comparison between post war rear seamed M1s, which do not have a stainless steel rim, should be quite straight forward.

Not too much can be said about the shell interior other than the maker markings. M1 helmets feature a blind heat stamp at the front around the peak area while M75s usual show a yellow ink stamp at the rear, such as U- SCH-76. Some M75s may also feature an extra metal clip next to the chinstrap bales for the purpose of holding the liner in place more securely.

Regarding chinstraps, while both are made of webbing with metal buckle mechanisms the details differ significantly. The M1 chinstrap is bar tacked to the bales with either a brass or black metal wire prong and buckle while M75 chinstraps are either bar tacked or cross tacked to the bales, with two brass wire snaps and an engineered buckle. If the M75 shell has a T1 chinstrap fastener then it is most likely an Austrian M57. The strap webbing on M75s also match the shell being green grey, while M1 chinstraps are tan or dark green.

Liners are a key feature to telling these two helmets apart. Made from green thermoplastic the M75 suspension is comprised of nine leather tongues, resembling that of the German M62, with the addition of a black leather US style chinstrap. The wartime M1 liner is made of brown resinated fibre with a webbing suspension and brown leather chinstrap. Later M1s also featured a webbing lining but in a different design configuration.

It must also be mentioned that while the Austrian M57 M1 clone is mostly identical to its replacement, the M75, the design of its chinstraps and liner reflect those used by the US during the 1950s.

It is hoped that this article can serve as a quick comparison between a run of the mill Austrian M75 and an original Second World War period US M1 steel helmet.

Instead of using original period helmets that are valuable and may become damaged from use on the set, many war films tend to use M1 helmet clones to resemble the famous WW2 helmet. Most of the times these are worn in background shots and good repros for close-up. Sometimes however, they are not pushed to the background and their tell-tale chinstraps give them away. The Austrian M1 clone is actually a good and cheap substitute for the American original, especially with its stainless steel rim.

At first glance the post war Austrian M75 steel helmet may appear to be a carbon copy of its Godfather, the original WWII US M1 helmet, upon which it was based. While both helmets feature many similarities, such as swivel bales, sewn on chinstraps and a stainless steel rim, it is the details of such that makes comparison between the two fairly easy.

If we focus on the shell first, it is easy to notice that the M1 features cork textured dark green paint as opposed to the M75 which is notable smoother and painted green grey in colour. The front peak and side flared rims on the M1 are more pronounced while the M75 also exhibits a slightly lower profile.

The stainless rims differ as well. On the M75 the rim is quite narrow and joins at the rear, while on the M1 it is wider and flatter, joining at the front. Comparison between post war rear seamed M1s, which do not have a stainless steel rim, should be quite straight forward.

Not too much can be said about the shell interior other than the maker markings. M1 helmets feature a blind heat stamp at the front around the peak area while M75s usual show a yellow ink stamp at the rear, such as U- SCH-76. Some M75s may also feature an extra metal clip next to the chinstrap bales for the purpose of holding the liner in place more securely.

Regarding chinstraps, while both are made of webbing with metal buckle mechanisms the details differ significantly. The M1 chinstrap is bar tacked to the bales with either a brass or black metal wire prong and buckle while M75 chinstraps are either bar tacked or cross tacked to the bales, with two brass wire snaps and an engineered buckle. If the M75 shell has a T1 chinstrap fastener then it is most likely an Austrian M57. The strap webbing on M75s also match the shell being green grey, while M1 chinstraps are tan or dark green.

Liners are a key feature to telling these two helmets apart. Made from green thermoplastic the M75 suspension is comprised of nine leather tongues, resembling that of the German M62, with the addition of a black leather US style chinstrap. The wartime M1 liner is made of brown resinated fibre with a webbing suspension and brown leather chinstrap. Later M1s also featured a webbing lining but in a different design configuration.

It must also be mentioned that while the Austrian M57 M1 clone is mostly identical to its replacement, the M75, the design of its chinstraps and liner reflect those used by the US during the 1950s.

It is hoped that this article can serve as a quick comparison between a run of the mill Austrian M75 and an original Second World War period US M1 steel helmet.

Modern Austrian Army ÖBH officer cap rank chart

Modern Austrian Army ÖBH officer cap rank chart

Understanding Austrian Army Peak Caps

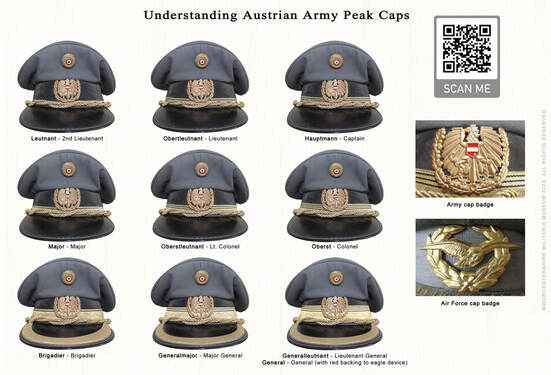

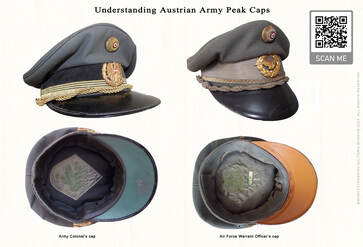

Peaked caps are used by all ranks of the Austrian military (Osterreich Bundesheer), which includes their air force. As such the detailing on the caps are relatively standard and branch and rank easy to identify.

The basic cap fabric consists of a top, band and peak, with a chinstrap and side buttons. The top is khaki grey with piping around the crown, with or without air vents. For army visors the band is black cotton for recruits and non-commissioned officers and felt for officers. Air force caps have a silver ribbon band. With both branches the chinstraps are twisted cord, reminiscent of those worn on Second World War German peaked caps. For recruits the chinstrap is corded fabric, while NCOs wear silverwire and officers goldwire. The chinstrap is held in place by two side buttons, which are either pitted or display the Austrian eagle national motif. White metal is used for NCO ranks and below, while officers wear a gilt version, made by Ulbrichts.

The peak is black for both branches and all ranks below that of Brigadier. Senior officers wear a single band of goldwire mounted to the peak topside. In most cases army caps feature a black rim around their edge and a green coloured underside. Vinyl is the material of choice on modern made caps. Air force caps reflect the moulded black patent leather pattern used during WWII, exhibiting a tan cross hatched underside, or are made from plastic. Cap linings are fairly standardised, consisting of a cloth lining with a narrow width leather sweatband. Situated in the lining's crown is a shaped transparent plastic sweat protector displaying the maker's details. Such as Frederich Weichelsdorfer, Sylvia Weichelsdorfer, Litto, or Maria Slama & Sons. The addition of a black HBA dated ink stamp is often found on NCO and recruit caps.